AFP, GABORONE

Botswana is this week holding a presidential election energized by a campaign by one previous head-of-state to unseat his handpicked successor whose first term has seen rising discontent amid a downturn in the diamond-dependent economy.

The charismatic Ian Khama dramatically returned from self-exile six weeks ago determined to undo what he has called a “mistake” in handing over in 2018 to Botswanan President Mokgweetsi Masisi, who seeks re-election tomorrow.

While he cannot run as president again having served two terms, Khama has worked his influence and standing to support the opposition in the southern African country of 2.6 million people.

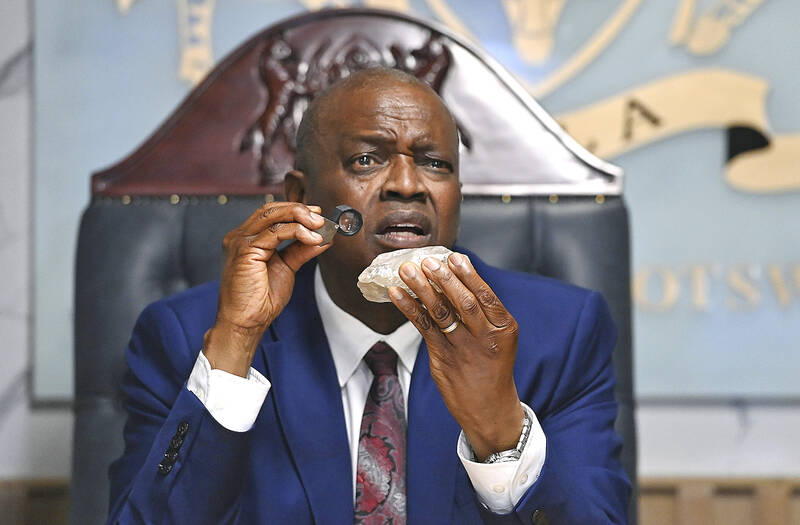

Botswanan President Mokgweetsi Masisi holds a 2,492-carat diamond that was unearthed at a local mine on Aug. 22 in Gaborone.

Photo: AP

“The return of Ian Khama has altered the political landscape. His gatherings are attracting large crowds across the country,” University of Botswana political scientist Zibani Maundeni said.

However, with the opposition divided, the eloquent Masisi is still expected to win. His Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) is the only party to have governed since independence from Britain in 1966. Under Masisi, Botswana’s economic growth has shrunk, suffering from weakened demand for diamonds — its main source of income — amid competition from lab-grown stones.

“The government continues to spend excessively, despite the declining revenues; we are reaching a crisis,” Maundeni said.

Unemployment has surged past 25 percent this year, with young people particularly affected, while the disparity between rich and poor is among the highest in the world, according to the World Bank.

“Citizens feel like they are not seeing much from the country’s mineral wealth,” said Tendai Mbanje, election expert at the African Center for Governance.

Khama is a “game changer,” analyst Adam Mfundisi said.

“In five years, the BDP under Masisi, wrecked the economy through corruption and maladministration,” he said.

The main opposition alliance is the left-leaning Umbrella for Democratic Change (UDC), led by human rights lawyer Duma Boko, 54.

“It’s been much too long to be operating under a system that has consistently produced the same, at best, mediocre results,” Boko said in an interview with South African channel ENCA in July.

However, the UDC’s clout has been weakened by the departure of the Botswana Patriotic Front (BPF) and Botswana Congress Party (BCP), which are each fielding their own presidential candidates.

Khama, 71, principally supports the BPF, founded by supporters when he dramatically quit the ruling party just months after Masisi took over as president, going on to win 52 percent at the 2019 elections.

As his feud with Masisi deepened, Khama fled to South Africa in 2021.

“I have to fix the mistake I made in appointing Masisi to be my successor,” he told reporters in March last year. “It was a huge mistake, one that we are regretting as a country, because he’s totally undermined democracy, human rights, the rule of law, interfered with the judiciary.”

Khama appears to have been stung by Masisi’s scrapping of some of his policies, such as a ban on elephant hunting and restrictions to his post-presidential benefits. In 2022, Botswanan authorities issued an arrest warrant against Khama on charges including unlawful possession of weapons. It was set aside by a court last month.

The move was perceived as a worrying “weaponization of law,” Mbanje said.

He also noted criticism of Masisi’s close relationship with Zimbabwe’s authoritarian president, Emmerson Mnangagwa, whom the opposition alleges is interfering ahead of voting day.

Analysts say that while Khama’s role should not be underestimated, his influence is limited to a few districts, including the center where he is a tribal chief.

“The nation is divided, with supporters on both sides,” political commentator Adam Phetlhe said.

“People who had high hopes that Masisi would deliver on his promises are now disappointed. Even if the BDP wins the upcoming elections, the margin will be small,” he said.